In June 1993 an ECT/ Sealand partnership at Rotterdam Delta Terminal opened the world’s first “robotized” terminal. Transport between quay and stack was conducted almost entirely by Automated Rail Mounted Gantry cranes (ARMGs) and Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs). Since then over 1,100 driverless stacking cranes are reported to have gone into operation worldwide and over 35 automated terminals have been launched (PEMA). The transition has been a steep learning curve, and with years of hard-won experience under the belt, port operators, analysts and executives have begun to understand the realities and challenges of automation far better.

A lack of software and technology standardisation, mismanaged market expectations, labour disputes, lower than expected productivity and initial terminal under-performance have hallmarked almost every port automation project. We will briefly examine some of these pain-points with a view to advancing necessary changes to the terminal automation conversation.

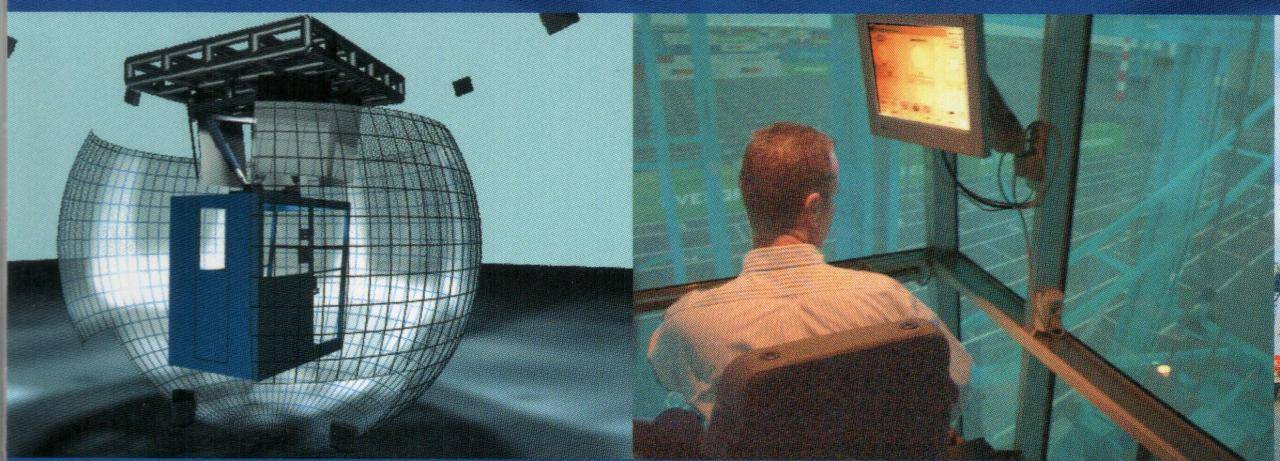

A note on definitions: when papers, pundits and owners refer to automated terminals they are typically only referring to: “automated movements in the yard and dock-yard interchanges like the ECT Delta Terminal. In such terminals, crane-ship operations are still manual whilst the interaction between yard cranes and the inland transportation means of reception and delivery remain assisted by remote controllers.” For the purposes of this paper we will refer to the full gamut of automation levels – from operator/crane decoupling in the form of remote operation, through fully automated horizontal container transport to terminals and OEMs striving to perfect supervised-operation/semi-automated RTG and quayside cranes.

Automation is not disruption

Port automation is not disrupting the sector. We are not dealing with an entirely new entrant that is upending the business model, in the way that for instance, Airbnb upended traditional hotel chains. (Should you wish to explore the distant-future of transportation logistics and delivery, perhaps start with Jeff Bezos’s plans to launch air hubs for mega-drone delivery bots). While port automation is not a disrupter in this sense, it is certainly true that converting to, or building an automated terminal is in every sense disruptive! We’ll argue that while there are aspects of this disruption that are unavoidable, other aspects can and are being managed successfully.

We will also try to frame and define port automation failure and indeed success.

Problem one: mix & match

The ports sector is by nature highly competitive, and by extension secretive. Being the first terminal or OEM to “crack the automation code” would frame an exceptional competitive edge. The irony however is that no single actor is going to crack the code, for the simple reason that a lack of standardisation in hardware technology, user interfaces, digital and software platforms is perhaps one of the greatest pain points for greenfield port automation projects to date.

Terminals planning greenfield automation projects would be only too happy to write a check and come back 5 years later to a fully functioning automated yard, and some OEMs are doing their level best to promote themselves as the “one-stop-shop”. However, reports from the trade press reveal that most terminals, for better or worse, are opting for the mix & match model.

At TOC EUROPE 2015, Frank Tazelaar, at the time managing director of APM Terminals MVII terminal in Rotterdam, himself at the time at the pointy end of their automated terminal development, spoke about the APMT approach in Maasvlakte II: a best-of-breed, mix-and-match style of procurement (World Cargo News 4/2015) where the terminal operator itself acts as an integrator, managing the efforts of a disparate group of vendors – automated equipment manufacturers, software and sensor vendors, TOS suppliers, and integrators. APMT approached this once more in similar fashion in their terminal in Tanger, albeit with different vendors and a different operating model.

What remains with the mix & match model is the need to integrate, almost on a project-by-project basis, which is inherently complicated and time-consuming.

Problem two: data, data, data

This is only the tip of the iceberg. The tantalizing promises of digitalization cannot be realized without data – accurate, diverse and clean – not to mention as much of it as possible. Persistent problems regarding data and knowledge sharing, accessing shipping and transport data, co-ordination with regard to platform development, and a “closed-source” mindset to developing port technology not only create serious delays in implementing port automation but more significantly cramps innovation. Even the World Economic Forum got involved, with a report that chides the shipping and ports sector for its slow digital uptake, and fragmented data sources.

As data is increasingly seen as the new gold, the question of who owns the data further hampers the sharing of data, since every actor in the supply chain wants to get the most out of “their” data, ignoring the greater potential of sharing.

Problem three: skills, staff, and disputes

Automation breeds discontent because jobs are being re-defined – as they are in many industries. This, however, is a deeply reductive way of looking at port automation. Here’s the longer view: container terminals – and by extension, their employees – are under a form of existential pressure.

While the global container terminal industry remains profitable – with projected annual EBITDA in excess of US$25 billion – growth is stagnating as the profile of global trade changes. In some cases, such as the China-US trade tariff dispute, it is changing quickly. In fact, economists at the WTO scrambled to amend what was quite a buoyant 2020 forecast for merchandise trade to something far more somber, six months later. Everything that we consider merchandise, typically apparel, appliances, and electronics, are shipped in containers. These products are usually produced using just-in-time protocols, and speed to market dramatically affects the prices they fetch. Furthermore, people are changing how, what, and where they buy, and manufacturers are following suit by producing closer to their demand-centres, utilizing digital-sales platforms and in the process reframing domestic supply-chains.

Shipping lines have responded to this demand pressure with a two-pronged approach: bigger ships and larger alliances. Today, just three alliances carry 80% of world trade in containers [2M: (MSC, Maersk, HMM), Ocean Alliance: (CMA-CGM, Cosco Group, OOCL, and Evergreen), and THE Alliance: (Hapag Lloyd, NYK, Yang Ming, MOL, K-Line)] (UCTAD 2019, Page 65). These behemoths can generally be more flexible and adaptable to market conditions, and unless regulators get involved, their dominance will persist. To make a rather long story short: shipping alliances have the economic power to impress enormous and expensive changes on terminals; infrastructure that accommodates larger ships and processes that make unloading those ships faster - such as automation.

Port workers and their unions are not foolish or under-informed. The logic is immutable: if the sector or the business suffers, so does job-security. However, managing the transition from strength to skill, from manual to automated and from mechanical to digital requires, well, a human touch. Cautionary tales abound in the automotive sector, none more so than the infamous Lordstown strikes that befell General Motors in the early 1970s. GM had just launched the world’s most mechanized assembly line, featuring amongst other technologies 26 welding robots. Critically, the company did not view these developments as a chance to ease the significant workload of assembly line workers and simply insisted that alongside the technology the line could proceed to produce 100 cars a day (60 cars a day being the industry benchmark at the time). It’s fair to say a catastrophe ensued: sabotaged cars recalls and $40 million in lost output. What’s interesting though is that in the aftermath, interviewers and analysts discovered that the workers did not have either a problem with the robots or indeed with their pay – in today’s terms Lordstown workers were earning over $28 per hour. The problem, as quoted by one of the strike leaders at the time was, “There’s more to it—how I’m treated. What I have to say about what I do, how I do it.”

The opportunity to add thought to one’s job, to master a new skill or puzzle out a challenge remains what makes our work-life interesting, on the production line, in the crane cabin and behind a keyboard. Automated ports will always still require the skills, insights, enthusiasm and experience that so many current workers can bring to the table. Additionally, automation and other associated developments can create a more challenging, dynamic, interesting and ultimately satisfying work-life. Communicating deeply and often about such changes was very-well handled by Hamburg Port, who would regularly include all workers in the port’s thinking and strategy.

Problem four: automation is not a silver bullet

The drive to automate is a commercial one – shippers are placing extraordinary pressure on terminals not only to accommodate ever-larger vessels, but to unload, and even deliver (relocate containers to an intermodal node), upward of 10,000 containers per vessel within 24 hours. The benefits of mega-vessels are also decidedly unequal. While shipping lines harvest the economies-of-scale benefits, ports pay the bulk of the price. A 2015 white paper by the International Transport Forum (ITF), forecast that mega-ships could add as much as US$400M annually to operational and CAPEX costs for terminals, with a third applying to equipment, a third to dredging and a third to port infrastructure (World Cargo News 6/2015). More recently McKinsey estimated in 2018 that ports globally have invested $10B in automating their terminals, notably more than predicted. With mega-ships occupying almost the entire shipyard order book, some figures demonstrate that without significant intervention, terminal productivity and shipping lines’ expectations will drift apart.

The figures below are taken from JOC’s port productivity report of 2019, which surveyed 7 of the 10 largest container shipping operators. The data covers nearly 200,000 port calls across 455 ports and compares the first half of 2019 with the first half of 2018.

Source: JOC; Port Productivity Report, October 2019

This exercise illustrates why urgent intervention in the capacity and productivity of terminals is required, and why so many terminal owners and operators are opting to automate many yard functions. Terminal managers expressed disappointment in the productivity yields of automation in the McKinsey report: The future of port automation. Sadly, the report does not use illustrative statistics and relies on generalized opinion. The standard tone, however, when terminals discuss automation, is one of impatience. Jan Cuppens, director of global engineering at DPWorld was unequivocal about STS automation issues at Tech TOC 2017 (TOC Europe 2017), saying that terminal automation is simply not delivering according to specifications. Semi-automation delivers, but with “far too many workarounds”, remote quay crane operation is “below expectations” and full automation is “far below expectations.”

By 2018 Mr. Cuppers was a bit more conciliatory. He presented a graph comparing manual and automated STS crane ramp-up times at two DP World terminals. Remotely operated STS cranes are, eventually, achieving their promised 30 moves per hour, but it is taking 21 months to achieve. “It is much too slow,” Cuppens declared simply – an echo perhaps of terminals’ frustrations the world-over.

Man-driven STS cranes (blue) and automated and remotely operated cranes (orange)

Source: TOC PresentationsThe issue therefore is not that automation is failing – AGVs have for years reached and exceeded performance expectations and longevity. The issue is the rate of implementation, and the timelines terminals can expect until previous levels of productivity are reached, and at what stage productivity will improve further.

The rate of automation implementation is a function of many things, yet the buck tends to stop with equipment OEMs. While this is not unfair, it is also not helpful. Ports, like ships, take a long time to change direction. Their organizational structure and information flows are siloed, and equipment and systems often work off disparate technology platforms of varying generations. Additionally, navigation systems, sensor and transponder distribution and software programming are location-specific, requiring OEMs to reinvent some spokes of their automation wheel with every terminal.

Why automation succeeds

Mega-infrastructure projects, by definition, have very many moving parts. Defining a path that takes each project in modular stages is a natural, and essential approach. Essential also is defining what absolute failure looks like. Fail fast is one of the defining features of the popular “agile” product development approach. Automation vendors, OEMs, and terminals need to negotiate timeframes and relationship structures that allow for this type of freedom.

Automation succeeds when terminals approach it as a journey of incremental, but sustained change. A defined path to automation approach allows terminals, even those with ageing fleets, to begin automating. Starting with smart features, terminals can choose from a range of operator-assisting technologies. Each enhancement brings that crane closer to its automation horizon. As terminals layer smart features onto their equipment, the system grows in an organic manner, allowing operators and managers to become increasingly familiar with the way the equipment functions. Eventually, the equipment is ready for supervised operation, and automated operation.

A second path that works is integration by single OEMs. Here the responsibility (but also the ability) to make it all work together shifts from the terminal operator to the OEM. Such an approach aligns well with a performance-based contract, extending well beyond the go-live of the terminal. The terminal operator and system integrator work together symbiotically to achieve a long-lasting, successful solution.

Port terminals are not yet hotbeds of innovation, and have been slow to adopt, and therefore benefit from, digital and automated processes, tools and equipment. Bullish shipping customers, stagnating throughput, high fixed costs and global policy pressure regarding sustainability are compelling port terminals to make bold leaps. Automation is one of these leaps. If terminals are to evolve into the more efficient, sustainable and profitable entities they promise to be, then automation is one of several key components for getting there. However, while pockets of excellence exist in both automation implementation and technology, there is always the danger of reverting to old-school, top-down, siloed thinking (from both terminals and vendors), a lack of vision regarding the digital horizon and a heavy-handed approach to change-management, all working to perpetuate an environment where automation, and associated terminal enhancements, are not yet thriving.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

Human Machine Interfaces - the key to productivity?

The journey of CONTROLS: DPW Antwerp